This is the first notable moment that calls this theme into play, and Urasawa does it so subtly and quickly but with enough weight to the words that readers can’t help but dwell on that little speech mistake.įrom this moment, Urasawa spirals out to deal with more of this theme of robot mortality and human connection to it in different situations. One notable worker, however, recalls the robot as Robby before quickly correcting himself to call it Patrol-Bot PRC Model 1332. Interestingly, a lot of the human characters have mixed or much more grey feelings about their relationships with robots, with some of the witnesses ignoring the fact completely.

When our protagonist, Gesicht, is investigating a human death, he finds out that a patrol robot died as collateral. However, Urasawa delves into the idea of the human/robot relationship heavily in this series, as it’s apparent that outside of a select few, humans don’t think of robots in a mortal sense. It’s here that we see one of the core themes of the story being established: Robots in this world live like humans, and some like Mont Blanc, are even treated with high regard. Urasawa immediately hits the ground running with this story, opening up with an environmental disaster and the death of one of the seven great robots of the world, Mont Blanc. “Pluto” is technically an “Astro Boy” story, but readers will really only have to know the usual cultural white noise about that character to get into this story.

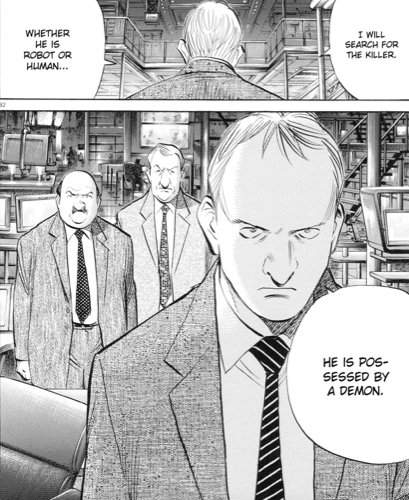

Europol’s top detective Gesicht is assigned to investigate these mysterious robot serial murders-the only catch is that he himself is one of the seven targets. In a distant future where sentient humanoid robots pass for human, someone or something is out to destroy the seven great robots of the world. Written, Illustrated and Lettered by Naoki Urasawa

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)